Notes to the 1968 Edition

Part One:In Search of Red China

Chapter 1:Some Unanswered Questions

[1]Written in invisible ink, the letter was given to me by Hsu Ping, then a professor at Tungpei University. In 1966, as for some years earlier, Hsu Ping was deputy secretary of the United Front Department of the CCP CC. In 1960, K'e Cheng-shih, then mayor of Shanghai, told me he had written the letter, which was authorized by Liu Shao-ch'i. (K'e died in 1965.) Liu Shao-ch'i was chief of the underground North China Bureau of the CC, and his first deputy was P'eng Chen. Others in his branch CC included Hsu Ping, Po I-po, Ch'en Po-ta, Hsiang Ching, Huang Hua, and Yao I-lin. See Biographical Notes——hereafter BN——pages 451-511. Abbreviations are given on page 441.

Chapter 2:Slow Train to "Western Peace"

[1]T'ai Chi-tao and Shao Li-tzu were Marxist-oriented members of the Kuomintang who formed a Communist study-group nucleus in Shanghai with Ch'en Tu-hsiu in 1920. Neither man joined the organization of the first CC in July, 1921. During the Second Civil War (1946'49), Shao Li-tzu supported the Communists against Chiang Kai-shek, and helped form the People's Republic of China. In 1967 he still held a seat in the NPC. See BN.

Chapter 3:Some Han Bronzes

[1]A genuine pastor, he was Wang Hua-jen, a member of the national executive committee of the Chinese Red Cross.

Part Two:The Road to the Red Capital

Chapter 2:The Insurrectionist

[1]This account, based on an interview with Chou En-lai and his comrades, was quite incomplete, but in 1936 it was fresh news to the outside world. Kyo Gizors, hero of La Condition Humaine (Man's Fate) by Andre Malraux, was said to have been based on Chou En-lai's role in this period. "Things happened quite otherwise, "according to Chou. See BN.

[2]Concerning such "old and patriotic gentlemen, "see Benjamin Schwartz's penetrating study, In Search of Wealth and Power:Yen Fu and the West (Cambridge, 1964).

[3]Other sources give lower estimates. For example, Harold Isaacs mentions 400 to 500 killed. (Mao Tse-tung told me in 1960 that Chiang Kai-shek's sudden "purge"in Shanghai and other centers, which caught the Party unprepared, killed about 40, 000 members.) Isaacs holds Stalin and the CMT largely responsible for the Shanghai deaths, since they refused to break with the KMT even after Chiang's men had begun killing Communists prior to the "Shanghai Massacre."See Isaacs, The Tragedy of the Chinese Revolution, pp. 165-185.

Chapter 3:Something About Ho Lung

[1]Inaccuracies in this colorful version of Ho Lung's life notwithstanding, it does parallel the main facts, and seems worth preserving as a contemporary firsthand impression by a comrade-in-arms. See BN.

Part Three:In "Defended Peace"

Chapter 1:Soviet Strong Man

[1]Properly Li T'eh, or Li T'e, according to Wade, but throughout the text Otto Braun's Chinese nom de guerre is transliterated as Braun himself wrote it. See BN.

[2]The remarkable Ma Hai-teh. See BN.

[3]Not including a family-arranged betrothal, which Mao ignored. In 1937 Ho Tzu-ch'en and Mao were divorced and in 1939 Mao married Chiang Ch'ing (Lan P'ing). See BN.

Chapter 2:Basic Communist Policies

[1]From Democracy, Peking, May 15, 1937, a brief-lived English-language anti-imperialist and anti-Nazi publication, edited by John Leaning. Among its associate editors (besides myself) were J. Leighton Stuart, president of Yen-ching University and later U.S. Ambassador to Nationalist China, and Soong Ch'ing-ling.

[2]See The Agrarian Reform Law of the People's Republic of China (Peking, 1952), and Ch'en Po-ta, A Study of Land Rent in Pre-Liberation China. Communist figures on tenancy have been questioned by J. Lossing Buck and other foreign agriculturalists. See Bibliography. For Ch'en Po-ta, see also BN.

[3]Part of this paragraph has been revised from my original text in order to include facts not fully known to me in 1937. The CCP until 1935 aimed at a complete overthrow of Kuomintang leadership and held that a "united front from below"could succeed only under its leadership of the masses against both the Kuomintang and the imperialists. The CC changed its policy at the Tsunyi Conference in January, 1935, when Mao Tse-tung proposed a united front to include all anti-Japanese elements (with Chiang Kai-shek and the right-wing KMT still excluded, however) and sought approval of that line from the CMT. In August, 1935, the CEC of the CMT adopted an anti-Fascist international-united-front line reconcilable with the Tsunyi decisions and going beyond them to include the national bourgeoisie. On that line the CCP built its united-front proposals of 1936. See Part Four, Chapter 6, note 3, and Wang Ming, BN.

Chapter 3:On War with Japan

[1]Mao's strategic views set forth here paraphrased his report to Party activists at Wayapao, in north Shensi, immediately following an important Politburo meeting held there, December, 1935, and formed the embryo of his later works, "Problems of Strategy in the Guerrilla War Against Japan, ""Problems of War and Strategy, "and "On Protracted War."See Selected Military Writings of Mao Tse-tung. These concepts, followed throughout the war against Japan, outline a general strategy of "people's war"which Mao later held valid against American armed expansion in Asia.

[2]Since Dr. Sun Yat-sen and the Kuomintang had always placed Taiwan among "lost territories"to be brought back under China's sovereignty, it seems hardly likely that Mao intended to concede future "independence"there. The CCP had never officially done so.

Chapter 5:Red Theater

[1]The "decadent"and "meaningless"Chinese opera died hard. Thirty years later the GPCR drafted opera stars wholesale to produce modern plays in forms which would "serve the people"by dramatizing revolution and the Thought of Mao Tse-tung, and which were not susceptible to undesirable historical analogies. The Red Lantern, a play of the 1960's popularized during the GPCR, was in content basically the same play as Invasion, of 1936——lacking only the comic relief of the marauding goats. (See Chiang Ch'ing, BN.)

[2]In his speech at the inception of the CPR (October, 1949) Mao Tse-tung declared, "China has at last stood up."

Part Four:Genesis of a Communist

Chapter 1:Childhood

[1]Mao did not mention the day of his birth, later reported as December 26. In 1949 Mao called upon the CC to ban the naming of provinces, streets, and enterprises after leaders and to forbid the celebration of their birthdays. See Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung (Peking, 1961), IV, 38.

Chapter 2:Days in Changsha

[1]Mao was nineteen when he entered First Teachers' Training School, which was for scholarship students only, who were expected to become primary-school teachers. "Humanism was the guiding principle, with emphasis on moral conduct, physical culture, and social activities. The First Teachers' Training School was the only Western-style building in Changsha. …… 'I have never been to a university, ' Mao recalled, 'nor have I studied abroad. The groundwork of my knowledge and scholarship was laid at the First Teachers' Training School, which was a good school'"(Jerome Ch'en, Mao and the Chinese Revolution, p. 32).

[2]Yang had an even greater influence on Mao's early interest in philosophical idealism than is acknowledged here. He was familiar with both Oriental and Western cultures, to a degree then rare among Chinese savants. His family were wealthy landowners of Hunan who could afford to give him a good education in the Chinese Classics and then send him to study for six years in Japan. At the age of thirty he went to Europe for another four years of study in Britain and Germany. That he chose to accept a post in a secondary institution indicated the high standing of the First Teachers' Training School. He went on to a professorship at Peking National University, where he continued to befriend Mao. Versed in Kant, Rousseau, and Spencer, Yang was also a follower of the Hunanese hero-patriot, Wang Fu-chih, a pragmatist philosopher as well as a warrior. Wang's seventeenth-century writings strongly appealed to Mao and other students of Yang who later became Communists, including Ts'ai Ho-sen (see BN). Yang is credited with having introduced Mao to Friedrich Paulsen's A System of Ethics. A copy of Ts'ai Yuan-p'ei's translation of that book still exists, with 12, 000 words of marginal notes in Mao's handwriting which reveal his admiration of Paulsen's emphasis on discipline, self-control, and will power (Ch'en, ibid., p. 44).

[3]Hsiao Yu (Siao Yu) wrote Mao Tse-tung and I Were Beggars. See Bibliography.

[4]Yi gave Mao, his former student, a job as principal of his "model"primary school, a satellite of the Hunan Normal School. Mao taught Chinese literature there until 1922. In 1965 Mao told me that at that time he really had had no ambition in life other than to be a teacher.

[5]Yi Pei-ch'i was himself "responsible"for the theft. He was director of the museum at the time the treasures disappeared, and Hsiao was his assistant. The treasures were later sold in Europe.

[6]In 1966-67, Mao encouraged the Red Guards of the GPCR to emulate such boyhood experiences, and to sally forth on "little Long Marches"of their own.

[7]Mao Tse-tung published an article in New Youth, April, 1917, under the pseudonym Erh-Shih-Pa Hua Sheng or "Twenty-eight-Stroke Student."(The three characters of Mao's full name are written with twenty-eight brush strokes.) His article, "A Study of Physical Education, "offers interesting insights into Mao's character at the age of twenty-four. Since the body itself "contains knowledge and houses virtue, "Mao saw perfect physical fitness as the foundation of mental perfection and, above all, will power. His article also glorified "military heroism."See Stuart Schram's translation, Une êtude de l'êducation physique.

Chapter 3:Prelude to Revolution

[1]Ch'en supported Wang Ching-wei's puppet government under the Japanese, became its premier after Wang's death, and was executed as a traitor by Chiang Kai-shek in 1946.

Chapter 4:The Nationalist Period

[1]Sneevliet had a long Indonesian background, and was a veteran member of the Second International. He supported Lenin's break with the older European Socialist International, to form the Third International. He was active in prewar revolutionary agitation in Indonesia and helped found a Social Democratic Party there. Back in Holland during the Second World War, he perished under the Nazi occupation.

[2]Chou Fu-hai ended by collaborating with the Japanese under the puppet premier, Wang Ching-wei (see BN).

[3]The Third CCP Congress confirmed the Sun-Joffe agreement, whereby Communists were to join the KMT, but the demand of Sneevliet, the CMT representative, that control of the labor movement should be shared with the KMT, was opposed by Chang Kuo-t'ao, then chief of the Orgburo and the Trade-Union Secretariat. Mao at first supported Chang Kuo-t'ao, but after the resolution was passed, by one vote, Mao adopted the Comintern view. Chang lost his post in the Orgburo, Mao succeeded him, and antagonism between the two men increased (Rue, Mao Tse-tung in Opposition, p. 38).

[4]In fact Mao's "coordinating"activities were so successful that he was attacked for "rightism"and expelled (for the first time) from the CC. His return to Hunan, "for a rest, "coincided with a reversal in CMT policy, now favoring separate CCP organization of labor. Mao was re-elected to the CC but Chang also recovered Party face (Rue, ibid).

[5]Official English translations of both works (FLP, Peking) show a few differences from the originals in Chinese, especially marked in the analysis of Chao Heng-t'i.

[6]Mao's Report, now a scriptural classic, stressed that "without the poor peasant there can be no revolution."Analysis of Classes in Chinese Society opens Mao's Selected Works, and is followed by the above Report (SW, Vol. I).

Chapter 5:The Soviet Movement

[1]Several important research studies of this period in recent years (see Bibliography) have assessed, in varying degrees, Stalin's responsibility for the "1927 debacle, "but Chinese historiography has yet to produce a documented analysis even from the official CCP point of view. Ch'en, Roy, and Borodin certainly followed directives from Stalin, who had taken control of the Executive Committee of the Comintern from Zinoviev in 1926. Thus it was Stalin's line which Mao here criticized by implication. Was Ch'en merely a scapegoat for Stalin's mistakes? In his own defense before the Emergency Party CC meeting of August 7, 1927, Ch'en asserted that he had opposed the CMT line in the spring of 1927, but that his protests were rejected; after that he had followed CMT discipline to enforce Stalin's directives despite his better judgment. (He had distrusted both Chiang Kai-shek and Wang Ching-wei.) After he was dropped from the PB, Ch'en circulated a letter to the CC in which he objected to its adoption of "defense of the U.S.S.R."as a duty taking primacy over all other revolutionary considerations.

In 1929 the issue had become critical when Chang Hsueh-liang seized the Russian-administered sections of the jointly owned Chinese Eastern Railway in Chinese Manchuria and declared them "nationalized."In retaliation, Moscow moved Red Army troops into Manchuria to restore Russian rights, while the Comintern demanded that the CCP (and all Communist parties) support Russian policy against the Chinese Nationalists. Ch'en was expelled from the Party in November, 1929, and later organized a "left opposition"party with Trotsky's support. That did not save him from arrest (and five years of imprisonment) by the Kuomintang authorities. Released in 1937, he died in 1942.

Borodin was recalled to Moscow in 1927 and for some years edited the English-language Moscow Daily News, with Anna Louise Strong as a coeditor. After the Second World War, Stalin had Borodin incarcerated and he died in Siberia. Stalin's police also imprisoned Anna Louise Strong, then deported her as an "American spy."Khrushchev ordered Borodin posthumously rehabilitated. He also ordered the rehabilitation of Miss Strong, who soon went to live in Peking, which became anti-Khrushchev headquarters. Roy remained in Stalin's good graces until 1929, when he suddenly left Moscow under an assumed name, and shortly afterward was officially expelled from the Comintern. (During the Second World War he led a pro-Hitler faction. in India.) Besso Lominadze and Heinz Neumann succeeded Roy and Borodin as Stalin's agents in China. Following Stalin's ambivalent orders, Neumann called for the Canton Commune (December, 1927), a failure for which Stalin held him personally responsible. He returned to Russia and was last seen there in 1931. In 1930 Lominadze joined the Opposition and tried to remove Stalin from CMT leadership. Stalin had him exiled to Magnitogorsk, where he soon committed suicide. Adolf A. Joffe, a veteran of the October Revolution who had served Lenin in arranging the Brest-Litovsk treaty before he negotiated the Sino-Soviet pact with Sun Yat-sen, committed suicide (1927) in protest against Stalin's expulsion of Trotsky from the Bolshevik Party.

Lominadze had been Li Li-san's strongest supporter in the Comintern. His attacks on Stalin were only partly connected with Chinese affairs but they coincided with a crisis in the "Li Li-san line"in China and helped influence Stalin to discredit Li and back a new leadership for the Chinese Politburo. Among Stalin's Comintern functionaries in China during this fateful period was Earl Browder, who was recalled from China by Pavel Mif. Browder was not expelled from the Comintern, however, which Stalin himself abolished with a stroke of his pen, in 1943.

[2]An interesting account of this incident, and the whole period, from the Left Kuomintang point of view, is given by T'ang Leang-li in The Inner History of the Chinese Revolution (London, 1930).

[3]Mao was not present during the Uprising but General Chu Teh credited Mao with having helped to plan it (Smedley, The Great Road, p. 200). A poster commonly sold throughout the PRC showed Mao speaking at a meeting (July 18, 1927) held near Nanchang, where decisions were made for the Uprising. Leading participants in the Nanchang Uprising included Chu Teh, Ho Lung, Chang Kuo-t'ao, Chou En-lai, Fang Chih-min, Li Li-san, Lin Tsu-han, Lin Piao, Liu Po-ch'eng, P'eng P'ai, Su Yu, Ch'en Keng, Ch'en Yi, Su Chao-cheng, Nieh Ho-t'ing, Nieh Jung-chen, T'an Chen-lin, T'an Ping-shan, Yeh Chien-ying, Hsu T'eh-li, and Teng Ying-ch'ao (Mme. Chou En-lai). The August 1 (Nanchang) Uprising came to be celebrated as the birthday of the PLA.

[4]Chingkangshan was a nearly impregnable mountain stronghold, formerly held by bandits, on the Hunan-Kiangsi border. For an account of the Communists' seizure of this mountain and their subsequent experiences there, see Smedley, The Great Road, pp. 225ff.

[5]Mao may have meant that he agreed with the "line"of the CCP Sixth Congress, while reserving for himself the thought that he did not agree with the Politburo's interpretation of it. In any case his statement to me was directly contradicted by his 1945 "Report on Some Questions in the History of Our Party, "made at the Seventh Congress of the CCP. In that long critique he identified three main mistakes of the Sixth Congress. The fundamental one was its failure to recognize that the "Chinese bourgeois democratic revolution is in essence a peasant revolution……"(SW, III, 177).

[6]The Ku-t'ien Conference, called by Mao when he was convalescing from a severe illness (he was at the time reported dead by the CMT), resulted in agreements which gave Mao's "Front Committee"political command over the entire Fourth Army. Mao's basic theses of revolutionary strategy and aims were:principal reliance on the support of the poor peasantry; the establishment of rural soviet bases; and the development of political and military organization and tactics learned from experiences on Chingkangshan which Mao had formulated at the two conferences held at Maoping. From this time on the Politburo opposition to Mao never quite succeeded in separating Mao from army and peasant support in the rural soviets.

Chapter 6:Growth of the Red Army

[1]Mao's sons were united with him at a later date. Yang K'ai-hui reportedly was offered the choice of repudiating the Party or death; she refused to recant. See Mao An-ch'ing, Mao An-ying, BN.

[2]As head of the General Front Committee, backed by army commanders Chu Teh and P'eng Teh-huai, Mao opposed the orders of the PB, headed by Li Li-san, to lead the second attack on Changsha. Mao was overruled by the Revolutionary Military Committee, and the September attack began. After a week of heavy reverses, Mao, Chu Teh, and P'eng "repudiated the Li Li-san …… policy of the CC"and ordered a general retreat. See Smedley, The Great Road, pp. 278-279.

[3]In Mao's published writings one finds only a few references to the Li Li-san period——which was really only one phase of a struggle for power between the urban-based CC and the rural-based soviets where Mao won a dominant position. Mao's laconic comment may now be supplemented, however, by much material uncovered concerning the whole series of differences (1927'35) within the Chinese leadership and between its various personalities and the Comintern under Stalin.

Generally, Mao's disputes with Moscow-oriented PB leaders revolved around his conviction that the land-hungry poor peasants were the "main force"of the revolution and that rural bases had to be built before the metropolitan areas could be encompassed and held. Those opposed to him tended to share Stalin's view of the peasants as primarily auxiliaries to be manipulated by the urban proletariat, the true "main force"of the revolution.

Fragments of the story may be found in the Biographical Notes about Ch'en Tu-hsiu, Ch'u Ch'iu-pai, Hsiang Chung-fa, Yang Shan-k'un, Li Li-san, Wang Ming, Po Ku, Lo Fu, Liu Shao-ch'i, Chou En-lai, Chang Kuo-t'ao, and Li Teh (Otto Braun). See also Ch'en Po-ta, to help fill out this brief summary.

From its inception the CCP accepted the discipline of a "democratic centralism"principle (acknowledged in the Party constitution) which re-required obedience to CMT directives on matters of overall strategy or "line."Within that concept the Chinese rural soviets and Red Army "combat Communists"under Mao's influence increasingly differed with the "dogmatists"and "theorists"trained in Moscow. It was not until January, 1935, that Mao finally won PB leadership from them when he delivered his Tsunyi critique of Po Ku, general secretary of the PB, and of Lo Fu, then chairman of a "council of commissars"of the Soviet Government. Po Ku and Otto Braun (CMT delegate) were downgraded by the revolutionary military affairs council, and the PB (under "Chairman"Mao) called for an anti-Japanese "united front, "with patriotic elements of all classes, seven months before the CMT did so. In 1936, however, Mao glossed over bitter intraparty quarrels when, in his interviews with me, he spoke of the "extraordinary ability and courage and loyalty"of such "revolutionary cadres"as Po Ku, Lo Fu, Teng Fa, Wang Ming, P'eng Teh-huai, and even Chang Kuo-t'ao. (See Appendices, p. 449.)

In 1927 Ch'en Tu-hsiu (see note 1, Chapter 5, above) had been found culpable for mistakes made by him under CMT directives. After the defeat of the Nanchang Uprising an ad hoc session (Emergency Conference) of the CC was called August 7. Held under the domination of a twenty-nine-year-old Georgian Russian CMT agent, Lominadze, the conference replaced Ch'en as general secretary with Ch'u Ch'iu-pai. New disasters then occurred at Swatow and in the December uprising in Canton. The latter was called by Stalin's CMT "expert"on uprisings, the German agent Heinz Neumann, aged twenty-six. Meanwhile, Mao Tse-tung had been expelled from the Central Committee and the Hunan Front Committee for "deviations"during and after the August uprising in Hunan.

In July, 1928, the CCP Sixth Congress was called in Moscow, under the wing of the CMT, also then holding its own Sixth Congress. Now Ch'u Ch'iu-pai was denounced and replaced by Hsiang Chung-fa, another choice of Lom-inadze's. Hsiang was a poorly educated Shanghai worker whom Lominadze used as a "proletarian"front man for Li Li-san, the "intellectual"who became chief of labor organization. With the backing of the CMT, Li Li-san returned to Shanghai, to find that Mao and Chu Teh were entrenched with their own peasant armed forces in rural soviets.

"The Sixth Congress recognized, "Li wrote to Mao (who had been restored to the Front Committee), "that there is a danger that the base of our Party may shift from the working class to the peasantry and that we must make every effort to restore the Party's working-class base."

Li's directives obliged Mao and Chu to try to use the infant Red Army to seize large urban areas, including an attack on Nanchang and two costly attempts to take and hold Changsha (1930). Mao and Chu Teh disobeyed Li's second order to attack Changsha. An anti-Mao clique in the Kiangsi provincial committee engaged in maneuvers to overthrow Mao. One eventual result was the Fu T'ien Incident (December, 1930), which Mao alleged was traceable to the "Li Li-san line."A brief and bloody localized intraparty war followed, coinciding with Mao's suppression of an "Anti-Bolshevik Corps."A number of Communists were killed and many alleged anti-Maoists reportedly were imprisoned. Most of them were "thought-remolded"——an early Maoist technique——and released.

Meanwhile, in Moscow, the CMT had prepared a younger generation of cadres to take over the leadership of Eastern revolutions. In 1925 the CMT had set up the Sun Yat-sen University. Among hundreds who studied there, only twenty-eight Chinese consistently supported Stalin during his struggles with Trotsky, Zinoviev, and Bukharin. These were proteges of Pavel Mif, whom Stalin made director of the university and chief of the CMT Far Eastern Section, after 1927. By 1930 Mif had built them into a hard-core "professional Bolshevik"elite schooled to take over China. Once called "Stalin's China Section"by their opponents, they later came to be known as the "Twenty-eight Bolsheviks."In 1930 their leader was a youth of twenty-four named Wang Ming (Ch'en Shao-yu), and his closest comrade was Po Ku (Ch'in Pang-hsien), aged twenty-three. Others of importance were Lo Fu (Chang Wen-t'ien), Shen Tse-min, Yang Shan-k'un, Ch'en Chang -hao, Chu Jui, Tso Ch'uan, and Teng Fa. Through the influence of the CMT they eventually exercised discipline over most of the "returned students"from Russia.

In mid-1930 Pavel Mif secretly returned to the sanctuary of the foreign-ruled International Settlement of Shanghai with Wang Ming, Po Ku, Lo Fu, Teng Fa, and other Stalinist disciples, who were introduced into the CCP CC. When they opposed Li Li-san, however, Li resisted Mif's maneuver and he and Hsiang Chung-fa dismissed Wang Ming and others from the PB, with the support of Chou En-lai. Mif secured Li's recall to Moscow, where Li confidently expected support from Lominadze. Unknown to him, Lominadze had become involved in a move to oust Stalin from the leadership of the CPSU and CMT. Li therefore found himself arbitrarily classified with the opposition and was silenced with it, by Stalin. He remained in disgrace and was not to return to China for some years. Although Hsiang Chung-fa remained nominal general secretary, Ch'u Ch'iu-pai was expelled from the PB and Chou En-lai retained his position only after a confession of error in supporting Li Li-san.

In July, 1936, at Pao An, Po Ku told me of Li Li-san:"His mistake was putchism. He favored armed uprisings in the cities, attempts to seize factories through armed struggle of the workers, collectivization in the soviet districts, capture of big cities by armed attack. …… Basically he denied the practicability of rural soviets; he considered that the Red Army should mobilize for storming of cities. …… He wanted Outer Mongolian forces to join in and support uprisings and civil war in Manchuria and North China. …… His mistake was that he insisted that China was, in 1930, …… the 'center of the world revolution, ' denying the Soviet Union as that center."Po Ku said that only he, Wang Chiahsiang, and Ho Meng-hsiung originally supported Wang Ming in his attempts to capture the PB leadership from Li Li-san (RNORC p. 16).

By January, 1931, Mif had (with Stalin's support) established Wang Ming in practical leadership of the CCP PB. In June, 1931, Hsiang Chung-fa's address was betrayed to KMT police by Ku Shun-chang, a Li Li-san sympathizer. Hsiang was executed in Shanghai. According to KMT police, the PB had Ku Shun-chang's entire family assassinated. Wang Ming then replaced Hsiang as general secretary in a PB which included Po Ku, Chou En-lai, Lo Fu, Han Ying, Liu Shao-ch'i, Lo Man, Meng Ch'ing-shu (Mme. Wang Ming), and Jen Pi-shih. (Mao was now a member of a CC branch or "Central Bureau"in Kiangsi.) Mif returned to Moscow, to remain in charge of the Chinese section of the CMT. Again the CMT line tended to harness the rural soviets to schemes of seizure of power by the urban proletariat. After the Japanese invasion of Manchuria (September, 1931), Wang Ming and his wife were recalled to help Mif in Moscow and Po Ku became PB general secretary. The PB now sent Chou En-lai, Chang Kuo-t'ao, Jen Pi-shih, and other members into various rural soviets north and south of the Yangtze, to enforce its directives. In the sanctuary of the foreign-ruled International Settlement of Shanghai, Po Ku maintained underground PB headquarters and sent directives to the 1931 All-Soviet Congress in Kiangsi, which he was unable to attend.

Hunted by the Shanghai police, who cut off sources of funds from Russia, Po Ku and Lo Fu finally moved the PB headquarters to Soviet Kiangsi late in 1932. They were reinforced by the arrival of a new CMT delegate, Otto Braun, known in China as Li Teh, a German with some military experience. Serious differences which had long divided the "Twenty-eight Bolsheviks"from Mao Tse-tung, chairman of the All-Soviet Government, chief commissar of the Red Army, and also a member of the PB, now erupted in a definitive struggle.

Chou En-lai became commissar general of the Red Army, but as Party general secretary it was Po Ku who matched forces with Mao for overall political leadership. Po Ku, junior to Mao by sixteen years, had never been in battle before he entered Soviet Kiangsi late in 1932, he told me, but he was armed with years of study of theory, dogma, and training in the use of Party control machinery. He also had solid CMT backing, with Li Teh at his side and Wang Ming, in Moscow, sitting in the shadow of Stalin. Strong in practical experience and popular support in the soviets and the armed forces, Mao lacked Po Ku's fluency in the scripture and techniques of CMT in-fighting, and had to tread warily to avoid open defiance of Moscow.

Invoking the prestige of the CMT and the "expert"military knowledge of Li Teh (who spoke no Chinese and voiced his views through Po Ku, as interpreter), Po Ku undermined the authority of both Chu Teh and Mao Tse-tung. By late 1933 Mao Tse-tung was excluded from PB policy making. In the defeated opposition, Mao was assigned the task of organizing the economy to meet Nationalist offensives (see SW, I, 129-137). While Chiang Kai-shek was diverted by provincial warlord rebellions, the Red Army expanded and the new PB strategy seemed successful. A debate over whether the Red Army should implement an alliance with the Nationalist Nineteenth Route Army during the Fukien Rebellion was closed out when the PB ruled against active collaboration even with anti-Japanese "bourgeois"armies and continued an uncompromising do-it-alone line, later denounced as left-deviationist.

Partly for his opposition to the latter policy, Mao was in 1934 also dropped from the all-powerful revolutionary military council, which included Chou En-lai, Po Ku, Li Teh, Lo Fu, Yeh Chien-ying, and Chu Teh. But Chu Teh was now subordinate to Chou En-lai as general commissar of the Red Army. Mao was suspended from the PB and may have been put under surveillance by the newly organized security police (modeled after Stalin's) headed by Teng Fa.

In those circumstances Chiang Kai-shek launched his well-prepared Fifth Extermination Campaign which ended in the defeat of the Red Army and the dissolution of Soviet Kiangsi. Mao blamed the catastrophe on the Party's failure to support the Fukien rebels (1933) and its reliance on positional warfare against Chiang, instead of following his tried and tested guerrilla strategy (as laid down at the Maoping Conferences) of "luring the enemy in deep"and declining major battles except with overwhelming superiority. Pro-Maoist commanders, resentful and distrustful of the seizure of power by the "Twenty-eight Bolsheviks, "and "obedient in word, disobedient in action, "may well have sabotaged the fine German battle plans of Li Teh, as he implied in remarks made to me in Pao An in 1936.

By October, 1934, the Red Army was hemmed into an area confined to six Kiangsi counties and was forced to evacuate its capital, Juichin. Li Teh, Chou En-lai, and Yeh Chien-ying drew up a plan of retreat; their first objective was to join Ho Lung's forces in Hunan. That plan was thwarted, with heavy losses, and the Reds then turned their columns into weakly defended Kweichow province, where they won a two months' breathing spell. After they captured Tsunyi, the summer capital, an emergency meeting was demanded by Mao Tse-tung, backed by a majority of the political and military officers of regimental units or higher. At an enlarged conference of officers and PB and CC members, Mao Tse-tung delivered a critique of the leadership which won him majority support. Mao was elected chairman of a new Party revolutionary military council (also termed military affairs committee), with Chou En-lai and Yeh Chien-ying retained. Chu Teh was confirmed field commander of the Red Army. Po Ku remained in the CC PB but was replaced by Lo Fu as general secretary. The office no longer carried the leadership, however; both military and political supreme command were now conceded to the Chu-hsi—— "Chairman"Mao. At Tsunyi the historic decisions were taken for the Long March to the Northwest.

Li Teh made the Long March as a guest adviser, but no longer invoked his CMT authority. In 1936, in Pao An, he told me that "the Chinese after all understand their revolution better than any foreigner could."Ch'en Yun was sent from Tsunyi to report decisions taken there to the Party in East China (headed by Liu Shao-ch'i?) and to Moscow. After Ch'en Yun's arrival in Moscow a meeting of the CMT elected Mao Tse-tung to the Central Executive Committee for the first time. Wang Ming continued as a resident delegate there in the CMT but Ch'en Yun was Mao's spokesman. Mao had won vindication and Stalin's practical recognition.

Moscow made no further attempts to intervene directly in Chinese Party affairs——with one exception. That was in December, 1936, during the Sian Incident, when Stalin cabled a threat, via Shanghai, to cut off all connections with the CCP unless it insisted upon Chiang Kai-shek's release, unharmed, from his captivity by Chang Hsueh-liang in Sian. (See RNORC pp. 1-5.)

Except for details based on the author's personal knowledge, the foregoing condensation of extremely complicated history may be filled out and documented by consulting basic research works listed in the Bibliography, especially Benjamin Schwartz's brilliant pioneer study, Chinese Communism and the Rise of Mao, and John E. Rue's recent and remarkably thorough interpretation, Mao Tse-tung in Opposition:1927-35. The CCP's official version of the period is largely contained in Mao's 1945 report to the Seventh Congress entitled "Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party"(SW, III, 177) and a few other references (SW, I, pp. 114 and 153); and in Hu Chiao-mu's Thirty Years of the Chinese Communist Party. Wang Ming's The Two Lines (Moscow, 1932, and Yenan, 1940) contains the main theses of the revolution as advocated and practiced by the "Twenty-eight Bolsheviks."

[4]Here, if not before, see note 3, above.

[5]The possibility of a move to the Northwest was undoubtedly debated at this time, but it was not until the Tsunyi Conference that decisions were taken to move there. See note 3, above.

[6]Such an offer was made and yet it was not implicated in the case of the Nineteenth Route Army, for reasons mentioned in note 3, above.

[7]Mao subsequently published his own close analysis of the tactical and strategic problems of all the Kiangsi campaigns. See SW, Vol. I, and Selected Military Writings of Mao Tse-tung. Communist analyses offered for both victories and defeats during the Kiangsi campaigns never adequately conceded the general strategic handicaps imposed on Chiang Kai-shek by preoccupation with his national defense responsibilities during Japan's invasion of Manchuria (1931), attack on Shanghai (1932), and military attrition in North China (1933), as well as with the warlords' war of 1930. For Chiang's estimate of the importance of such factors, see his Soviet Russia in China, pp. 62-64.

Part Five:The Long March

[1]This was the first detailed account of the Long March to be published, and was based largely on eyewitness testimony of many participants (reflecting their heroic view of the retreat), as gathered in direct personal interviews. Official and nonofficial versions of the epic have since become available (see Bibliography). The Long March became ever more glorified in Communist propaganda, so that it may be years before fact can entirely be separated from fiction. It is now evident that the plan of retreat was largely improvised until the armies reached Tsunyi, where Mao apparently won approval for his "destination Shensi"concept which became the Long March. By the 1960's Peking's new Museum of the Revolution devoted a whole floor to historical relics, montages, and recapitulations of the Long March. The display included a very large electrically illuminated and animated map showing the route of the heroes. Every fifteen minutes a young girl, her hair in a pony tail, picked up a pointer and began to recite a stage-by-stage account of the adventure to ever waiting crowds, wide-eyed and open-mouthed, gathered below her. One of the features of the museum was a motion film made by the author of the arrival of the survivors in Kansu, the only one of the March.

Chapter 1:The Fifth Campaign

1. See especially Yang Chien's The Communist Situation in China, published in Nanking under the auspices of the Kuomintang-sponsored Academy of Sciences. Yang's report concedes the Communist reforms mentioned, as part of an analysis of Red successes among the poor peasants. For a recapitulation of "Red terror"charges see Chiang Kai-shek's Soviet Russia in China. Mao Tse-tung's Report on an Investigation into the Peasant Movement in Hunan describes activities carried out by Communist-led peasants against "local bullies, ""bad gentry, "and "corrupt officials"for whom the "only effective"suppression was "to execute …… at least some of those whose crimes and wrongdoings are most serious."(SW, I, 38.)

[2]See note 1, above.

[3]Some very extensive interview material elicited in response to my questions to Wu Liang-p'ing, Hsu T'eh-li, Lo Fu, Chou Hsing, and others concerning matters of life, death, and taxes in Soviet Kiangsi was omitted from this book, for the reason stated——that I had no experience there on which to base a judgment——but was later published in RNORC.

[4]Smedley, The Great Road, p. 309.

[5]These Red remnants, after a rebirth as the New Fourth Army, developed into the very large force that crushed Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalists in Central China a decade later. See Ch'en Yi, BN.

Chapter 2:A Nation Emigrates

[1]As far as I know, that "collective account"was never published.Chapter 4:Across the Great Grasslands. The dramatic duel between Mao Tse-tung and Chang Kuo-t'ao, to which brief reference was made here, was the last major challenge to Mao's Party leadership for about three decades. In 1936 I had but fragmentary information concerning the nature of the split. Chang Kuo-t'ao later denied that Chu Teh stayed with him involuntarily. Among others who remained with Chang in Sikang was Li Ching-ch'uan (see BN). In 1960, when I asked Mao Tse-tung what was "the darkest moment of his life, "he said it was the struggle with Chang Kuo-t'ao, when the breakup of the Party and even civil war "hung in the balance."See Chang Kuo-t'ao, Li Hsien-nien, T'ao Chu, BN. For details of the Mao-Chang struggle and Chang's flight to KMT China, see RNORC.

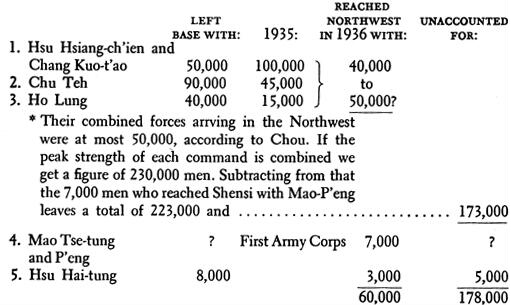

[2]The following is partly based on a conversation with Chou En-lai at Pao An; diary record dated September 26, 1936:

Chou says that the greater part of the Red Army losses took place in Szechuan, Kweichow, and Sikang. Losses due to actual fighting with the Kuomintang forces were less than those from fatigue, sickness, starvation, and attacks from tribesmen.

About 90, 000 armed men left Kiangsi with the main forces. Of these 45, 000 had been "lost"by the time the Red Army crossed the Chin-sha River into Szechuan. Meanwhile Hsu Hsiang-ch'ien left the Oyuwan area in 1934, with between 50, 000 and 60, 000 troops. When he had been in Szechuan six months he increased his forces to more than 100, 000. Late in 1935 Ho Lung left Hunan with about 40, 000 troops. He reached Sikang with not more than 20, 000, more likely 15, 000.

On the arrival of the three armies in Szechuan, therefore, the figures were roughly as follows:

LEFT OLD BASE WITH | STRENGTH IN SZECHUAN | LOSSES | |

|---|---|---|---|

Firsh Front Army: Chu Teh-Mao-Chou | (1934)90,000 | 45,000 | 45,000 |

Fourth Front Army: Hsu Hsiang-ch'ien-Chang | (1933)50,000 | 100,000(+50,000) | ? |

Second Front Army: Ho Lung-Hsiao K'e | (1935)40,000 | 15,000 | 25,000 |

A total of 160, 000 men, of whom more than half were (1935) under Hsu Hsiang-ch'ien and Chang Kuo-t'ao, while the Kiangsi-Hunan forces had lost 70, 000 men en route (1934 and 1935).

In 1935 the First Army Corps (First Front Army) arrived in Shen-pei with about 7, 000 men. There it joined Liu Chih-tan's force of about 10, 000. Hsu Hai-tung also came up from Honan in 1935 with 3, 000 troops left out of a starting force of 8, 000. New enlistments in Shen-pei (north Shensi), Shansi, Kansu and Ninghsia resulted in approximately the following:

| First Army Corps (arrived from Szechuan with): | 7,000 |

| Shen-pei troops under Liu Chih-tan (later used as replacements): | 10,000 |

| Hsu Hai-tung forces from Oyuwan: | 3,000 |

| Shansi enlistments on 1935 expedition; | 8,000 |

| New enlistments in Shen-pei, and deserters from Manchurian and Mohammedan armies: | 7,000 |

| Approximate strength of regular forces in Northwest now: | 35,000 |

| Partisans and Red Guards in all Shen-Kan-Ning: | 30,000(estimate) |

Chou En-lai estimates the present strength of the Second Front and Fourth Front armies now en route to north Kansu, all the survivors from the winter in Sikang, as between 40, 000 and 50, 000.[*] What, then, has happened to the rest of the troops?

| Shen-pei troops under Liu Chih-tan | 10000 |

| New enlistments in Shansi | 8000 |

| Enlistments in Shen-pei and Kansu-Ninghsia | 7000 |

| 25000 |

The above figures would suggest a total combined loss in all Red armies over a period of a little less than two years of about 180, 000 men. …… My guess would be that the present* Red strength may not exceed 30, 000 to 50, 000 regulars, with no more than 30, 000 rifles.

Comment added in 1967:

The peak strength (1934-35) of the three main armies was 230, 000, consisting of the First Front Army, commanded by Chu Teh and Mao Tse-tung (90, 000), the Second Front Army, commanded by Ho Lung and Hsiao K'e (40, 000), and the Fourth Front Army, commanded by Chang Kuo-t'ao and Hsu Hsiang-ch'ien (100, 000). Chu Teh's army was divided at Moukung during the Mao-Chang dispute, after which Mao, P'eng Teh-huai, Chou En-lai and Lin Piao proceeded to Shensi where they arrived with only 7, 000 men. A year later Ho Lung and Hsiao K'e reached Szechuan and met Chang Kuo-t'ao's surviving forces. The two Front armies proceeded northward but not as a coordinated operation. Chu Teh, Ho Lung, and Hsiao K'e arrived at Kansu and were met by P'eng Teh-huai, when their combined regular forces probably were no more than 40, 000. Meanwhile, Hsu Hsiang-ch'ien, obeying Chang Kuo-t'ao's orders, followed a different route with the intention of occupying northwestern Kansu and seizing the road to Sinkiang. Hsu's army was trapped by KMT troops west of Sian, badly mauled, and split in half. The northern column, led by Li Hsien-nien and renamed the West Front Army, proceeded toward Sinkiang. Heavily attacked by Chinese Moslem troops with greatly superior numbers and arms, Li reached Urumchi with only 2, 000 survivors. Hsu Hsiang-ch'ien and Chang Kuo-t'ao were cut off from their own remnant forces and arrived in Yenan sick and accompanied only by their personal bodyguards. Rupture of communications and coordination between Chang and Yenan, and then the split between Chang and Chu Teh and Ho Lung——and even some armed skirmishes between the two Party factions——had left the Fourth Front Army isolated and an easy prey. In brief, after my conversation with Chou En-lai, in September, 1936, Chang Kuo-t'ao's once formidable army of "100, 000"virtually disintegrated before his part of the Long March ended early in 1937.

[3]The "three armies"were the First, Second, and Fourth Front (see note 2, above). Mao later rewrote the poem, of which several translations now exist.

Part Six Red Star in the Northwest

Chapter 1:The Shensi Soviets:Beginnings

[1]Thirty years later Mark Selden published a detailed and absorbing study of the origins of the revolution in Shensi, based on extensive and newly unearthed research data, entitled, "The Guerrilla Movement in Northwest China, "China Quarterly, Nos. 28-29 (Oct.-Dec., 1966, Jan.-March, 1967).

[2]Mao Tse-tung gives a different version of this incident in his SW, Vol. I.

Chapter 3:Soviet Society

[1]See Mao Tse-tung, "How to Differentiate the Classes in the Rural Areas, "SW, I, 137-139.

Part Eight:With the Red Army

Chapter 1:The "Real"Red Army

[1]Joseph W. Stilwell was in 1937 U.S. military attachê in China. He became commander-in-chief of U.S. forces in the China-Burma-India theater during the Second World War. See The Stilwell Papers (New York, 1948).

Part Nine:With the Red Army (Continued)

Chapter 4:Moslem and Marxist

[1]"Feudal"and "backward"the ruling Ma family indeed was, as this report of three decades ago attests, but to conclude that the Communists easily convinced the Hui-min that they had nothing to fear in a future Socialist state would be greatly to minimize the troubles which lay ahead. Schisms among the Red troops themselves proved as serious as the quarrels then rife among the "three faiths"and the four Mas and their subjects. Such divisions led to serious Red defeats (see Chang Kuo-t'ao, Hsu Hsiang-ch'ien and Li Hsien-nien, BN). Not until the Liberation War were the Ma brothers finally driven from the Northwest.

The Communists did keep their promises to create autonomous Mohammedan states in Ninghsia and Sinkiang, but religious leaders continued to resist communization. Behind their smoldering discontent, which broke out in sporadic revolts after formation of the CPR, was the Hui-min's fear of loss of their grazing lands to Chinese farmers, and absorption such as overtook the Mongols of Inner Mongolia. The CCP policy toward minority nationalities was in many respects far more enlightened than anything pursued under the Kuomintang, but ancient quarrels between the Chinese and their frontier peoples were not to be settled in a generation or two. On their part, the Russians exploited signs of instability behind such Chinese frontiers after the breakdown in Sino-Soviet relations from 1960 onward.

Part Ten:War and Peace

Chapter 2:"Little Red Devils"

[1]On my return to China in 1960 and 1964-65 I met several former "little devils"holding positions of major responsibility. One was T'ai Ch'un-ch'i, vice-director of the Institute of Venereology and Skin Diseases, whom I first knew in 1936. In the same institute I renewed old acquaintance with Dr. George Hatem (Ma Hai-teh), an American, and the only foreign doctor with the Communist forces since 1936. See BN.

Chapter 3:United Front in Action

[1]See Part Eleven, Chapter 6, note 1.

Chapter 4:Concerning Chu Teh

[1]Retained to preserve the form and spirit of the original text, this sketch is based chiefly on biographical notes given to me by Commander Li Chiang-lin (who was on Chu Teh's staff from the earliest days in Kiangsi), supplemented by brief data from Mao Tse-tung, P'eng Teh-huai, and others. It contains many inaccuracies but, as in the case of the story of Ho Lung, may be regarded as part of the Red Army legend at a time when no documentation was available. See BN.

[2]More accurate versions of Chu Teh's relations with Fan Shih-sheng later appeared in Smedley, The Great Road, and Rue, Mao Tse-tung in Opposition.

Part Eleven:Back to Pao An

Chapter 1:Casuals of the Road

[1]Communists continued to observe a tolerant policy toward foreign missionaries throughout most of the Resistance War, but foreign missionary activity was ended soon after the CPR was established. See TOSOTR for some details.Chapter 2:Life in Pao An

[1]The wife here referred to arrived with Li Teh from Kiangsi. Later he divorced her and married an actress from Shanghai. Li Teh left his second Chinese wife behind when he climbed aboard the one and only Soviet Russian plane that landed in Yenan during the Resistance War.Chapter 3:The Russian Influence

[1]Consult Part Four, Chapter 6, note 3 in connection with this chapter and the two chapters following.Chapter 4:Chinese Communism and the Comintern

[1]This chapter is retained to preserve the form of the original book. Its inadequacy reflects the poverty of information available thirty years ago, and should be read in contrast with annotations such as Part Four, Chapter 6, note 3.

[2]In a general sense this assessment still has validity in retrospect, but it reflects a limited knowledge of complex Sino-Russian Party relationships at that time. Direct contact with Moscow was indeed often lost for months, but conformance with the Comintern's general line and directives was the expressed intention and constant preoccupation of the Chinese PB. Not until after the Tsunyi Conference of January, 1935, did Mao's national leadership prevail over Russian-trained and Russian-oriented Chinese Communists. Mao never openly denied the supreme wisdom of Stalin until twenty years later.

Chapter 5:That Foreign Brain Trust

[1]The "Red military council, "as constituted in 1934 and headed by Chou En-lai, was not "unanimously"opposed to Li Teh's plans. The "so I was told"above referred chiefly to a statement made in Kansu (August 12, 1936) by Hsiao Ching-kuang, who blamed the "Kiangsi disaster"on attempts to fight positional warfare during the Fifth Campaign. "This was largely due to Li Teh's advice, "he told me. "He was very confident and very authoritative. He pounded his fist on the table. He told Mao and others that they knew nothing about military matters; they should heed him."How was he able to do that? "He had the prestige of the world Communist supporters behind him."See RNORC.

Chapter 6:Farewell to Red China

[1]The Red reports of victory given to me proved premature. The "joyous reunion, "while doubtless genuine enough between the rank and file, opened a new chapter of reckoning for differences which had divided the camps of Chang Kuo-t'ao and Mao Tse-tung in the Party leadership. For comment on Red losses reported later, see Hsu Hsiang-ch'ien, Chang Kuo-t'ao, and Li Hsien-nien, BN.

[2]In Mao's earlier interview with me (July 16, 1936) he had proposed a "united front"with "all anti-Japanese forces, "but not specifically a coalition with the Kuomintang Government itself. The "immediate"cause of the change was doubtless the decision of the Central Committee based on newly received interpretations of the proceedings of the Seventh Congress of the Comintern.

[3]When I left the Red areas I sent back my camera and some film to Lu Ting-yi, as promised——by hand of the courier, Wang Lin——on condition that Lu would supply me with newsworthy photographs from time to time. The only picture he ever got to me was an enlargement of what he considered his masterpiece, some Shensi apple blossoms.

Part Twelve:White World Again

Chapter 1:A Preface to Mutiny

[1]Wang later headed a Japanese puppet government. See BN.

Chapter 3:Chiang, Chang, and the Reds

[1]The limitations and purposes of this kind of coalition regime were set forth by Mao Tse-tung in The New Democracy (Yenan, 1938).

[2]Although the Communists had "nothing to do"with the actual physical seizure of Chiang, personnel in their liaison group in Sian at the time probably had prior (though perhaps very brief) knowledge of the plan. Captain Sun Ming-chiu, the young Tungpei officer whose troops "arrested"Chiang, was under strong Communist influence. As noted earlier, Chang Hsueh-liang had CCP CC members in his own headquarters and Wang Ping-nan (see BN) was personal secretary to General Yang Hu-ch'eng, whose troops participated in the "arrest."

The Communist delegation sent from Pao An to Sian to negotiate immediately after the incident included, besides Chou En-lai (then vice-chairman of the Revolutionary Military Committee):Yeh Chien-ying, chief of staff of the "Anti-Japanese Red Army, "and Po Ku, "Minister of Foreign Affairs"of the Communist provisional government. After this book was published I was told by Po Ku (in 1938) that Chou En-lai was the only one of their delegation who saw the Generalissimo in Sian. Po Ku said that in Chou's single brief interview no agreement was signed and Chiang merely expressed sentiments in favor of ending the civil war, which Chou interpreted as a moral commitment. Shortly afterwards, to their disappointment, the Young Marshal released the Generalissimo without informing Chou or the other Communists. According to Po Ku they had hoped that the Generalissimo would remain in Sian long enough at least to reach concrete terms of a truce agreement on the basis of which to restore a united front of national resistance. Further evidence concerning the incident (referred to in RNORC, pp. 1-15) indicates that the Communists in Yenan debated a public trial for Chiang Kai-shek. Any such intention was certainly abandoned after a message reached the Communists directly from Stalin, in which he threatened publicly to disown the CCP unless they demanded Chiang's release unharmed, a message which was said to have greatly annoyed Mao. I know of nothing, however, to support the view that Mao Tse-tung ever demanded the "execution"of the Generalissimo, a view attributed to me without foundation by Stuart Schram in Mao Tse-tung, p. 199.

[3]See RNORC.

[4]While this account seemed plausible to me on the basis of information available at the time, I now believe that the idea of a "popular trial"may have been debated by the Communists, who repudiated it for reasons mentioned in note 2 above.

Chapter 4:"Point Counter Point"

[1]Chiang Kai-shek never forgave Chang Hsueh-liang and never freed him. Thirty years later Chang was still Chiang Kai-shek's personal prisoner on Taiwan.

[2]For documentation of the official Communist position throughout the Sian affair, see SW, Vol. I, pp. 255ff.

Chapter 6:Red Horizons

[1]Report to the Communist Party (Yenan, April 10, 1937). See SW, Vol. I. Mao's frank declaration should have destroyed all notions that he sought to establish anything less than all-out proletarian (Communist-led) power. Not many months later, in an interview with me, Mao even more categorically derided any deviation from that 100 per cent Communist aim. (See Appendices, Further Interviews with Mao Tse-tung, p. 447.)